Building Pictures

About the Exhibition

Work by:

Alexander Apóstol

Dionisio Gonzalez

Terence Gower

Luisa Lambri

Chris Mottalini

Bas Princen

Thomas Ruff

Josef Schulz

Architects and photographers both transform space, yet they approach their tasks from opposite directions. Generally speaking, the architect’s practice moves from two dimensions into three, and the photographer’s from three dimensions into two. For the most part the architect imagines and renders spaces that do not yet exist, and then shepherds them into being. The photographer, conversely, documents things that already exist in time and space and abstracts them into flat depictions. When a photographer takes an architect’s finished product and transforms it, both the concept of the original place in its idealized, drawn form, and the formal reality of its existence converge into one image.

Since the development of photography, architects have well understood this dynamic. Many, for this reason, have taken an intense interest in how their buildings are presented in photographs. Le Corbusier, famously, often airbrushed away all of the contextual information from photographs of his buildings, such as plants and the surrounding terrain, before he allowed them to be published. And even today, the term “architectural photography” generally means work made with a large-format camera that corrects perspective—straightening out all the lines in pictures that celebrate the architect’s vision and depicts the building in factual terms.

Modernism is the first movement in the history of art to be intertwined with photography, its information shared and education achieved largely through photographs.

The development of photography had a much more general impact on the trajectory of modernist architecture. Modernism is the first movement in the history of art to be intertwined with photography, its information shared and education achieved largely through photographs. Architects and laypeople alike feel they know a building through pictures of it rather than through personal experience or conventional books. Thus, as scholars such as Beatriz Colomina have observed, the site of architecture has grown increasingly displaced from the site of actual construction, and ironically, ephemeral photographs have actually made some architecture more permanent because they solidify its place in history.

The artists in this exhibition are not architectural photographers in the traditional sense. Rather, they use architecture as subject matter to comment on its social and political implications, its history, and its relationship to perception—how it is that the aesthetics of space are communicated. They address the difference between architecture and its photographic representation directly, often treating them as entirely separate realities. They understand photography’s difficulty in translating the grandeur of a space with its simultaneous tendency to clean up content and overlook messy details. Their works open up a new experience, sometimes based on the tension between the intentions of the original design and the realities of the place and its transformation over time.

These works open up a new experience, sometimes based on the tension between the intentions of the original design and the realities of the place and its transformation over time.

Some of the artists in this exhibition make photographs of well-known architecture and in the process underscore the fact that although we feel secure in our knowledge of these buildings, most of what we know is derived from photographs. In the photographs from his l.m.v.d.r. (Ludwig Mies van der Rohe) series, Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958) transforms well-known views of famous houses using digital tools, disallowing the photograph’s tendency to purify a building visually and reduce it again to line and shape, particularly when shot from a distance that includes the building’s full elevation. By radically shifting color and blurring the famously straight, clean lines, Ruff makes the image less static and documentary, reminding us of the energy these structures still possess as well as the progressive, spirited ideas that inspired them.

Terence Gower (Canadian, b. 1965) explores the architecture of Luis Barragán, the famous Mexican architect who used color to transform the International Style into a more sensuous experience. Gower’s El Muro Rojo (2005-06) is an installation: one black-and-white photograph, a 2005 retake by Jorge del Olmo of the famous image of the Casa Barragán roof patio taken by Armando Salas Portugal, hangs on one bright red wall. Obviously concerned with capturing the phenomenology of the place, Gower translates the visceral experience of viewing a Barraágn building firsthand by attempting to reconcile the immersive, powerful experience of standing in front of a huge brightly colored wall with that of looking at an abstracted, black-and-white photograph. Luisa Lambri (Italian, b. 1969) also looks at Barragán’s home, and reinterprets his design by focusing on the small details and the light pouring through the window. Like Gower, she is interested in an intimate and subjective, rather than an objective, cold, or comprehensive description of a place.

Chris Mottalini (American, b. 1978) also takes domestic structures designed by a famous architect as his subject, in this case Paul Rudolph, and focuses on their neglect and disrepair. Rudolph studied with Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and became a well-known late modernist architect who blended minimalist shapes in dynamically complex ways and used light to create delicate steps and risers that appeared to float. His most famous works include the Yale Art and Architecture Building, the Government Center in Boston, and the Lippo Center in Hong Kong. Mottalini focuses on homes Rudolph designed, capturing them in a state of neglect and disrepair just before they are torn down, symbolic perhaps of the perceived failures of the utopian ideals of modern architecture. His work provides detailed records of the structures, as well as a sad commentary on the lack of foresight in terms of historic preservation.

Alexander Apóstol (Venezuelan, b. 1969) also looks back at seminal architecture, but transforms it to comment on social ideals. In his series Residente Pulido, he takes landmark 1950s rationalist modernist buildings in his native Venezuela, built during an extremely prosperous time when Venezeula’s oil economy was booming, and digitally removes any access to the buildings, sealing off doorways and windows. The architecture becomes an unsettling monument to past splendor, a point that is heightened by Apóstol’s titling of each piece with the name of a famous porcelain maker. The buildings appear at once fragile and solid, suggesting the inherent tenuousness of the wealth and grandeur of the 1950s, as well as the imposing, macho nature of the heavy design. Dionisio Gonzalez (Spanish, b. 1965) also confronts social issues by piecing together images of the favelas, or shanty towns of São Paulo, Brazil into long panoramas to which he adds bits and pieces of pristine, contemporary architecture. Very much a reaction against the government project Proyecto Cingapura, a re-urbanization scheme meant to provide better living conditions to the favela residents that has recently been criticized for not maintaining its buildings and not living up to its goals, Gonzalez conceives of his works as proposals for new social centers. Instead of imposing a systematic, orderly structure from an outside urban planner, Gonzalez’s structures reflect the spatial order that already exists in these neighborhoods, one that is chaotic and in flux.

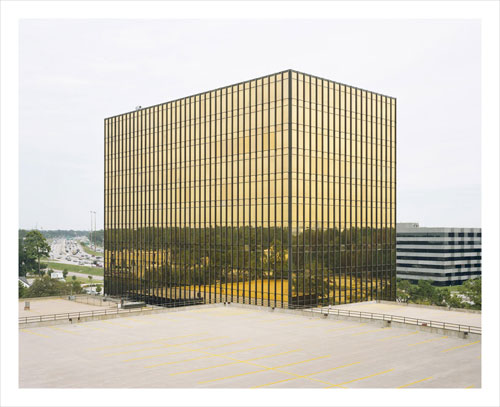

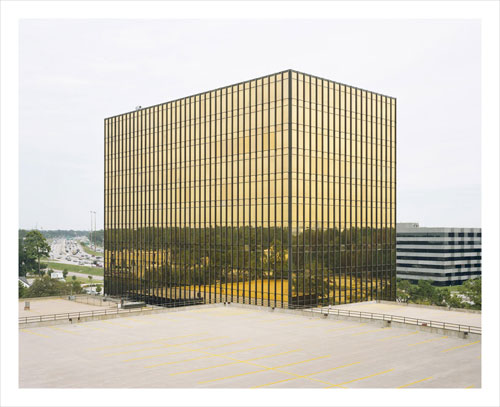

Like Apóstol and Gonzalez, Josef Schulz (German, b. 1966) digitally transforms pictures of buildings, in his case mostly generic industrial structures that he finds in the landscape. Schulz reduces information and plays with color so the buildings appear to be graphically idealized, closer in their appearance to a drawing or a 3-D rendering made by an architect. He removes all the specifics of location and function, giving the buildings a semi-abstracted, futuristic, and strangely quiet feel. Bas Princen (Dutch, b. 1975), by contrast, tells us exactly where his pictures are taken. But despite this his images feel otherworldly. His picture of the ring road or a building in the outskirts of Findeq, near Ceuta, Morocco are so spare and clinical that they feel surreal and model-like. Technical choices such as reflections that connect to background elements complicate any sense of depth, and along with a soft, ethereal palette, give these places a strange, powerful atmosphere that hints at a fourth dimension—architecture’s mythical status.

—Karen Irvine, Curator

Image Gallery