Art, Activism, Policy, Power: Documenting Migration Stories in Portraits and Interviews

Art, Activism, Policy, Power is a program that connects MoCP exhibitions and collections with high school students to help them discover how artists use research-based creative practices to make change in their communities. In Fall 2024, students from South Shore College Prep, Prosser Career Academy, and Lincoln Park High School will work with artists Regina Agu and Dawit L. Petros to create photographic portraits and interviews of people in their families, neighborhoods, or social circles, to capture stories about how they arrived to Chicago.

About the Teaching Artists

Working in photography, video, printmaking, and sculpture, Dawit L. Petros delves into histories in East Africa (especially his home country of Eritrea, as well as Ethiopia and Libya) and how they connect to Chicago.

Regina Agu works in large photographic installations, books, and film to present parallels between the Black Southern landscape and the Great Lakes regions through histories of the Great Migration. As a child of maternal Creole and Black American heritage, and paternal Nigerian migration, her process uniquely depicts the American last century’s “Up South” migration legacy via the qualities of landscape, shore, and historicized memory.

Introductory questions for discussion:

Both Agu and Petros express stories of people migrating from one place to another in their artwork. Are there any people in your life that moved to Chicago from a place that is very different from this city? How might an artist express stories differently from the people who lived the experiences?

Why do you think Chicago is a beacon for migrating or displaced communities?

Image Gallery

What does it mean to be an artist activist?

There are many forms of activism that range from more vocal and active demonstrations to organizing boycotts, divestments and protests to simply becoming more knowledgeable and spreading awareness of the different paradigms and systems of oppression in place historically and today.

It perhaps is not as common to think of compassionate listening as a form of activism. In this approach, taking time to ask questions and learn from people in our communities about what is important to them, where they came from, and what challenges they face can be a deeply effective way to extend love and care to your surroundings and de-center a culture of separateness.

Artists have the potential to creatively collect and weave together community memory. When engaging with other people’s stories, it is important to slow down and be present and intentional with your interactions. You are giving people a platform to share stories that may have otherwise gone unheard, and with that comes responsibility.

Questions for discussion:

What forms of activism have you seen, taken part of, or felt drawn to?

Besides compassionate listening, what are some other forms of sustainable activism?

Policy: Connecting histories

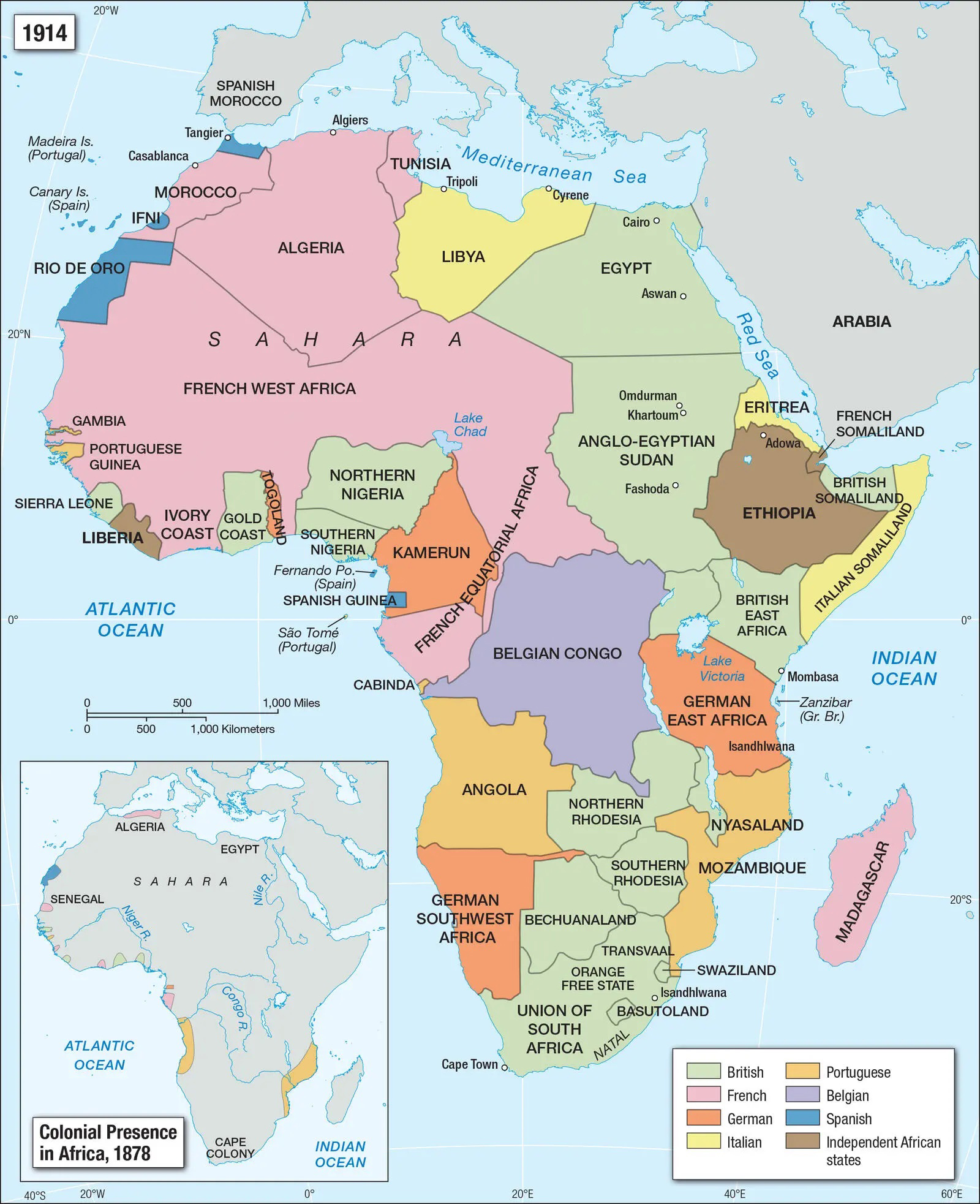

Dawit L. Petros’s work informed by the history of European colonization in Africa and how it shaped global migration. From 1833 until 1914, 90 percent of the African continent was under European rule, as countries raced to pillage resources like gold, silver, rubber, palm oil, and later, cotton at the expense of the livelihood of local communities.

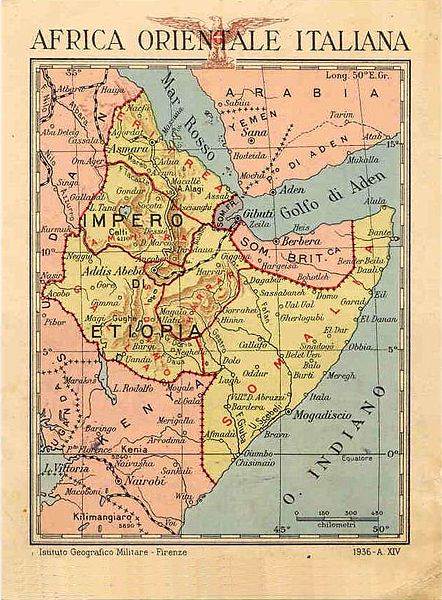

In around 1885, Italy began colonizing parts of East Africa, first in present-day Eritrea and parts of Somalia with intent to expand into what was then the Ethiopian Empire. Ethiopia defeated Italy in the First Italo-Ethiopian War from 1895-1896, and the countries again were at war from 1935-1936, when Italy consolidated Ethiopia with Eritrea and Italian Somaliland into the province of Italian East Africa.

During World War II, Italy lost control of its colonies in Africa. In 1952, the United Nations placed Eritrea under control of Ethiopian Empire, which has since been the root of many conflicts. As a result, between 1965 and 1991, roughly one-quarter of Eritreans fled the Horn of Africa due to war, famine, political unrest, and persecution. By the year 2000, 30,000 Eritreans lived in the United States—many of them in Chicago.

Questions for discussion:

According to the Vera Institute, in 2023: “1.7 million immigrants reside in Chicago, or 18 percent of the total population. One in three children in Chicago has at least one immigrant parent.”

The history of war and colonialism outlined above is just one example of how political forces in one locations can shape the demographic makeup of neighborhoods and communities across the world. What other global histories might shape the way you live in and experience Chicago?

Image Gallery

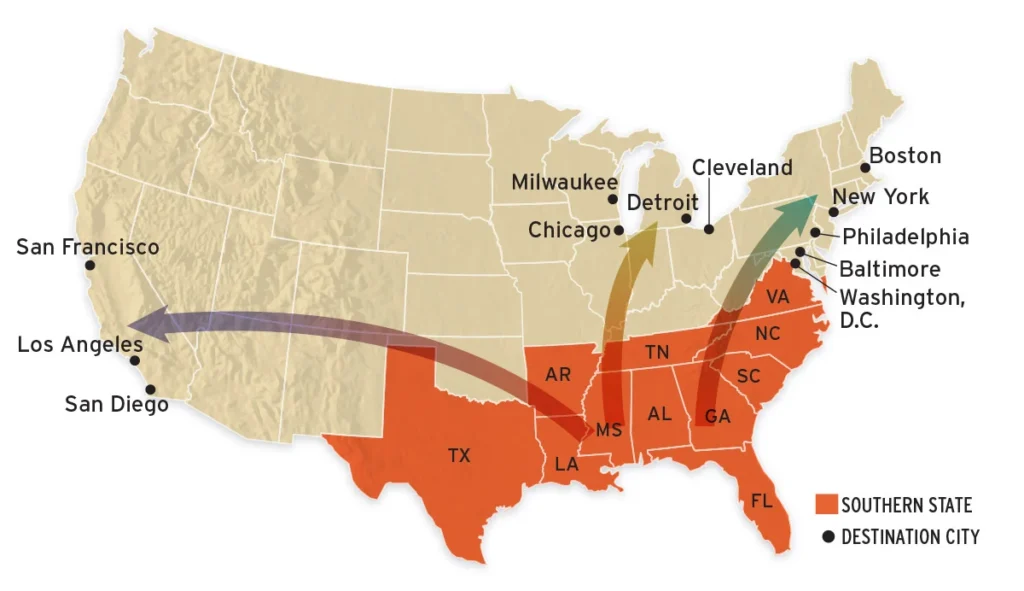

Regina Agu’s work is informed by the history of the Great Migration, which occurred in the US from 1915 until 1970. During this time, an estimated six million Black Americans left the segregated Jim Crow South for more opportunities and more freedom. During the first wave of the migration, people traveled by railway, with Chicago as one of its primary routes. Later, after the addition of the interstate highway system, people were able to more easily travel across the country by bus. Chicago was a destination throughout, and the city was permanently transformed, with its population of Black residents growing from just two percent of the overall population in 1910 to 33 percent by 1970.

Questions for discussion:

Are there any ways you see the American South represented in Chicago today, such as in food, architecture, or cultural traditions?

Accents, sayings, and slang vary across the United States. For example, the way people speak in Chicago, New York, or Los Angeles can differ widely from southern cities like New Orleans or even East African communities. How might the Great Migration or Immigration have had an affect on regional African American Vernacular English (AAVE)?

Where are people in your neighborhood from? For how many generations have they lived there?

Create your own archive

Now that you know a little more about the artists you will be working with, it’s time to think about how you can add your voice. The prompts below will help guide you in creating photographic portraits and oral history interviews that capture migration stories in your community.

Please also contribute your personal history to our collective migration map here.

Identify who to interview

Working in groups, have students discuss who they know in their families, neighborhoods, or social circles who have moved to Chicago from another city, state, or country. Ask them to write down as many names as they can identify, pushing them to think about whose stories they believe most strongly should be seen and heard. What do they already know about the person? How comfortable will they be inviting them to participate in this project? How accessible is the person they want to photograph and interview? Are there any privacy concerns? For example, will the person be open to having their story shared in a gallery and online? Was the person a part of any significant history that you want to highlight? What research can you do on that history so you can ask questions that draw out these lived experiences?

Set up a location to photograph

Before inviting a person to be photographed, take some time to consider where the photograph should take place. What is seen in the background of the image can potentially give a lot of information and say a lot about the person in the photograph. Will you photograph them in their home? Please of work? Outdoors in a location that is significant to them?

Also make a plan for what time of day you would like to photograph. If photographing outside in the early morning or early evening, your lighting will appear more golden and romantic than if you photograph in mid-day when the sun is bright (and the person may be squinting). If you are photographing indoors, are there ways to adjust the lighting so that the camera can more accurately capture details in the setting?

And finally, once your person has arrived and you are about to photograph, consider how they should sit or stand. What do you want their body language to communicate? Will you show their whole body or just their head and torso? If there are privacy concerns, can you make a portrait of someone by photographing an object they own, or obscuring their face from view?

Create an oral history recording of their migration story

Either before, during, or after making the photographic portrait, ask your participant questions about their story that you can share as a component of the final artwork presentation. Excerpts from the interview can either be presented as text panels that accompany the portrait (such as in Jess T. Dugan’s To Survive on the Shore series) or as a QR code that someone could scan with their phone to play and listen to while they look at your portrait.

Before recording, write out a list of questions you plan on asking. Try to avoid “yes and no” questions and instead ask open-ended questions that will get the person sharing more details about their life. For example, instead of saying: “Did you like Chicago when you first moved here?” You could say: “Tell me how you felt when you first arrived to Chicago.”