Dorothea Lange and the Documentary Tradition

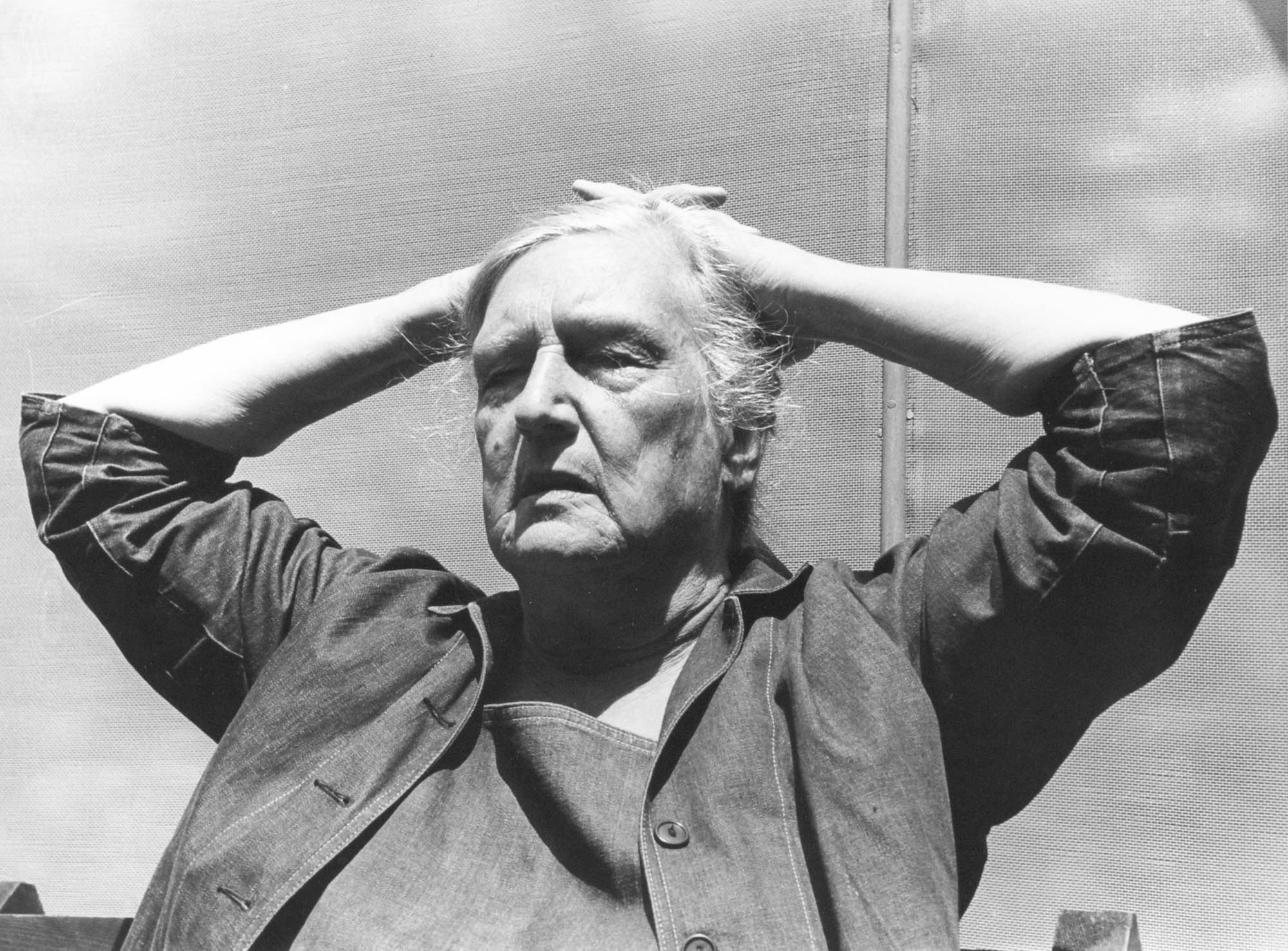

Dorothea Lange (United States, 1895-1965) believed in photography’s ability to reveal social conditions, educate the public, and prompt action. Though she is best known for her depression-era photographs that came to shape our view of one of the most tumultuous eras of American history, Lange’s career was long and varied. Her keen interest in the lives of ordinary people led her to travel and photograph diverse subjects across the U.S. and around the world. The MoCP holds over 500 original works by Lange from a generous donation from Katharine Taylor Loesch. Taylor Loesch was the daughter of Dorothea Lange and economist Paul Schuster Taylor (1895-1984), Lange’s collaborator and second husband.

This curriculum guide focuses on Lange’s work documenting the Dust Bowl for the Farm Security Administration. A downloadable version can be found here.

The museum is generously supported by Columbia College Chicago, the MoCP Advisory Committee, individuals, private and corporate foundations, and government agencies. The materials here are excerpted from resources created through the Terra Foundation for American Art’s American Art at the Core of Learning initiative. Terra Foundation staff contributed to this guide. Excerpts of this curriculum have been posted by PBS in conjunction with the American Masters documentary Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning.

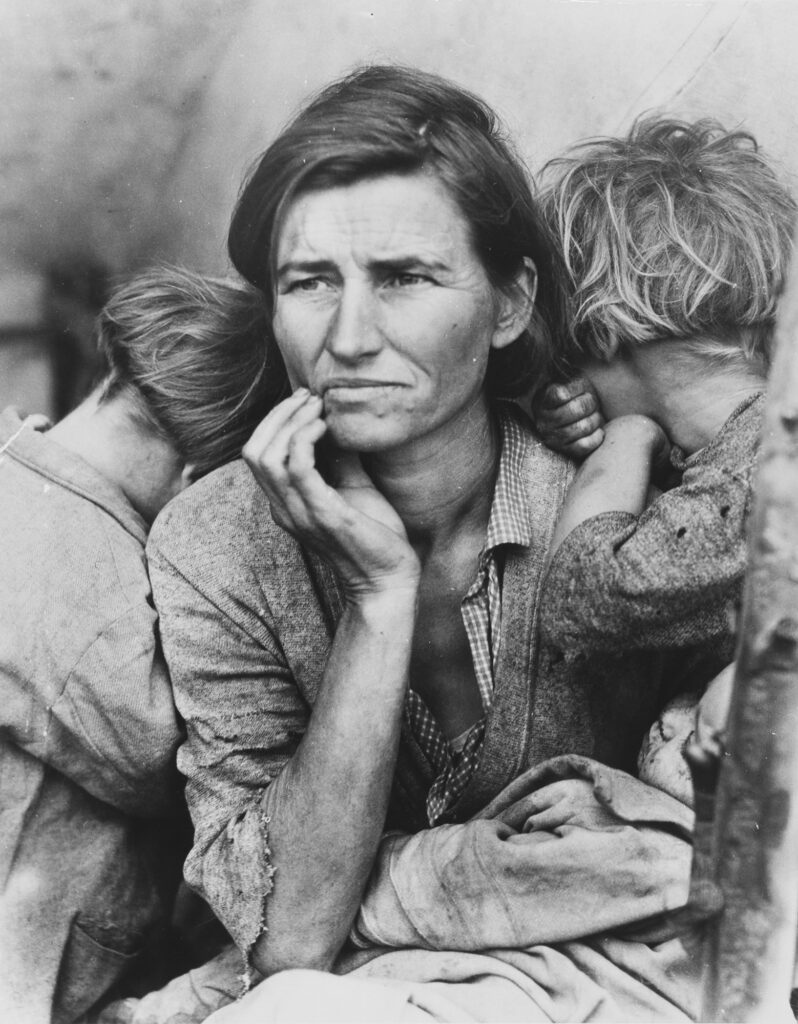

Examining an Icon

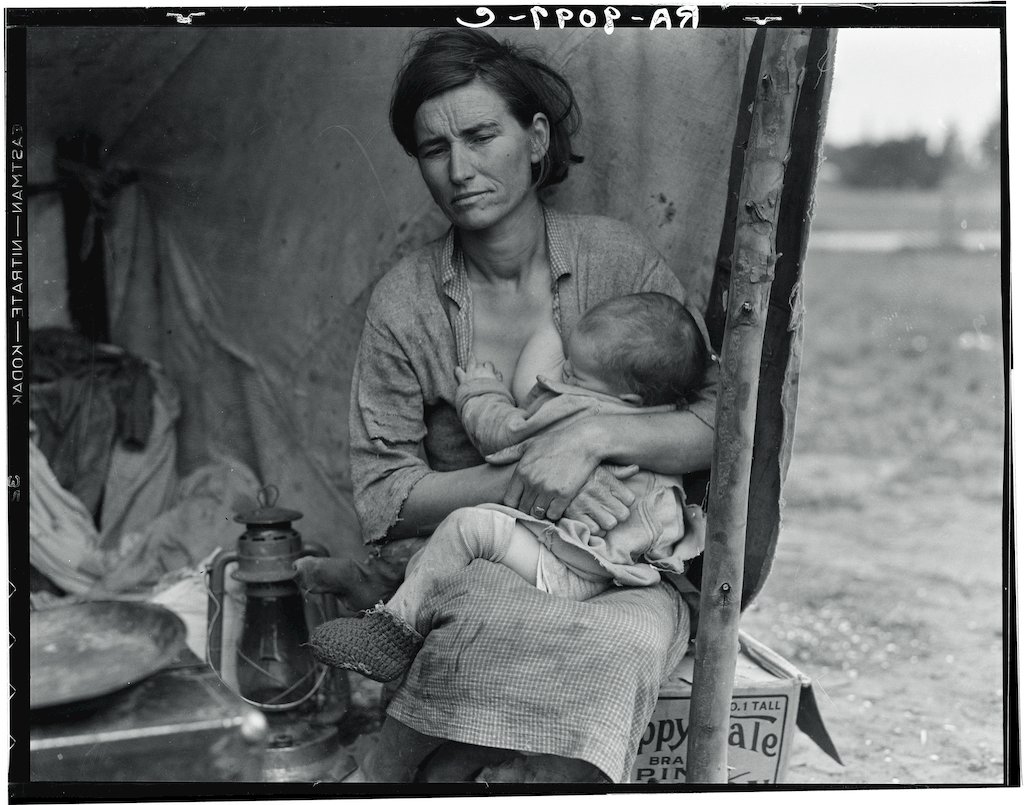

This image made by Dorothea Lange in 1936 is one of the most widely published images in the history of photography. Although the photograph is now known as Migrant Mother, the full title Lange gave was in a longer notation style. It reads:

Migrant agricultural worker’s family. Seven children without food. Mother aged thirty-two. Father is a native Californian. Destitute in a pea pickers camp because of the failure of the early pea crop. These people had just sold their tires in order to buy food. Most of the 2,500 people in this camp were destitute. Nipomo, California.

Closely examine Migrant Mother, considering the following questions:

- Where does your eye go first? Where does it go next? Why?

- What can you tell about how the photographer made the picture?

- What do we learn about the people in the photograph? How?

- Can you tell where and when this image might have been made? If so, how?

- What is the mood or feeling of the image? How is that communicated?

- What do we know for certain?

- What assumptions might we have made?

- Can you tell how the photographer feels about her subjects? If so—how?

- Do you feel any personal connections to this work? Explain.

Adding Cultural Context: Lange, the Dust Bowl, and the Great Depression

The Dust Bowl

From around 1930-40 the southwestern Great Plains region (that encompassed the western parts of Kansas, southeastern Colorado, the Oklahoma Panhandle, the northern Texas Panhandle, and northeastern New Mexico) suffered a severe drought and devastating winds. Misleading information about the agricultural potential of the land led farmers to use improper farming techniques that exacerbated the vulnerability of the land. Low crop prices and high machinery costs also led to increased vulnerability. Poorer farmland was utilized since the farmers needed to cultivate more land, which led to the depletion of much needed nutrients in the soil and increased the regions susceptibility to drought. Those who couldn’t leave had to endure the severe dust storms, emotional and financial stress, and general uncertainty around their future. The effects on the region lead the federal government under Franklin D. Roosevelt to enact relief programs through the New Deal. Relief included providing emergency supplies, cash, establishing health care facilities and government-based markets for farm goods, providing the right technology and advice to appropriately farm on the land, along with many other relief measures. The population, through determination, dignity, and optimism, was able to survive one of the worst droughts in American history. To learn more about the dust bowl and about life on the camps and farms you can visit the Library of Congress here. [1]

[1] https://drought.unl.edu/Dustbowl/Home.aspx

The Great Depression

Dorothea Lange created thousands of photographs to document the poor conditions of Americans during the Great Depression (1929–1939), the period after the stock market crashed which led to little business activity in the United States and around the world. Lange photographed workers on strike, people living on the street, and hungry families waiting in line for food. Migrant Mother was just one of many images of the hundreds of thousands of desperate farming families who were forced to leave their homes in search of work, as seen in some other images Lange made during this time here.

Some farmers couldn’t make enough money to keep their lands because of the struggling economy. Other farms were abandoned because of the horrible dust storms and a lack of rain. The dust and drought made the land impossible to use in sections of Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, and Kansas, a region that came to be known as the Dust Bowl.

In 1935 the United States government created the Farm Security Administration (FSA), an organization to help those most affected by the Great Depression. The FSA hired photographers including Lange to record the difficult conditions in rural America during the time in images. These photographs, like Migrant Mother, were used to help convince Americans that people, especially those migrants camping near rural farms, were suffering and needed help. While many of the FSA photographers pursued their individual interests in what they photographed; they were ultimately working on assignment for the US government. Their images were used in part to promote government programs and were eventually archived in the Library of Congress. The FSA photographers did not have control over how the images they created were reproduced, distributed, or archived.

Shortly after Migrant Mother was made, the photograph was printed in the San Francisco News with the title “Ragged, Hungry, Broke, Harvest Workers Live in Squaller”, on March 10th, 1936 [squaller is another spelling of squalor] As a result of the image, the government rushed 20,000 pounds of food to the camp where the family stayed. It is now one of the most famous images of the Great Depression, and one of the best-known and most widely published photographs ever made.

The Documentary Tradition

To be a documentary photographer is to faithfully and accurately capture people, places, objects, and events throughout history. Photographers such as Eugene Atget, Lewis Hine, and Gordon Parks are three exemplar artists who have worked in the documentary tradition, each in their own distinct way. Eugene Atget set out to photograph the streets of Paris and the everyday scenes in order to form an encyclopedic mass of images of Paris on the brink of modernity and the images were supposed to act as source material for other artists. Lewis Hine’s social documentary work depicted issues of child labor, harsh realities of the laborer, and immigration. Gordon Parks focused on issues such as poverty, race relations, and civil rights as he photographed a segregated America. As seen here, the photographer is tasked with packing the frame with information that educates the viewers as well as preserving those places, objects, events, and people in time.

Questions for Discussion:

• What can photography do well in creating a record or document? What are its limitations?

• In what ways can documentary photographs be “truthful?” How could a documentary photograph be misleading?

• What are some of the rights and responsibilities of those who tell the stories of others through photographs or words?

• What kind of power dynamics do you think are involved in making documentary images?

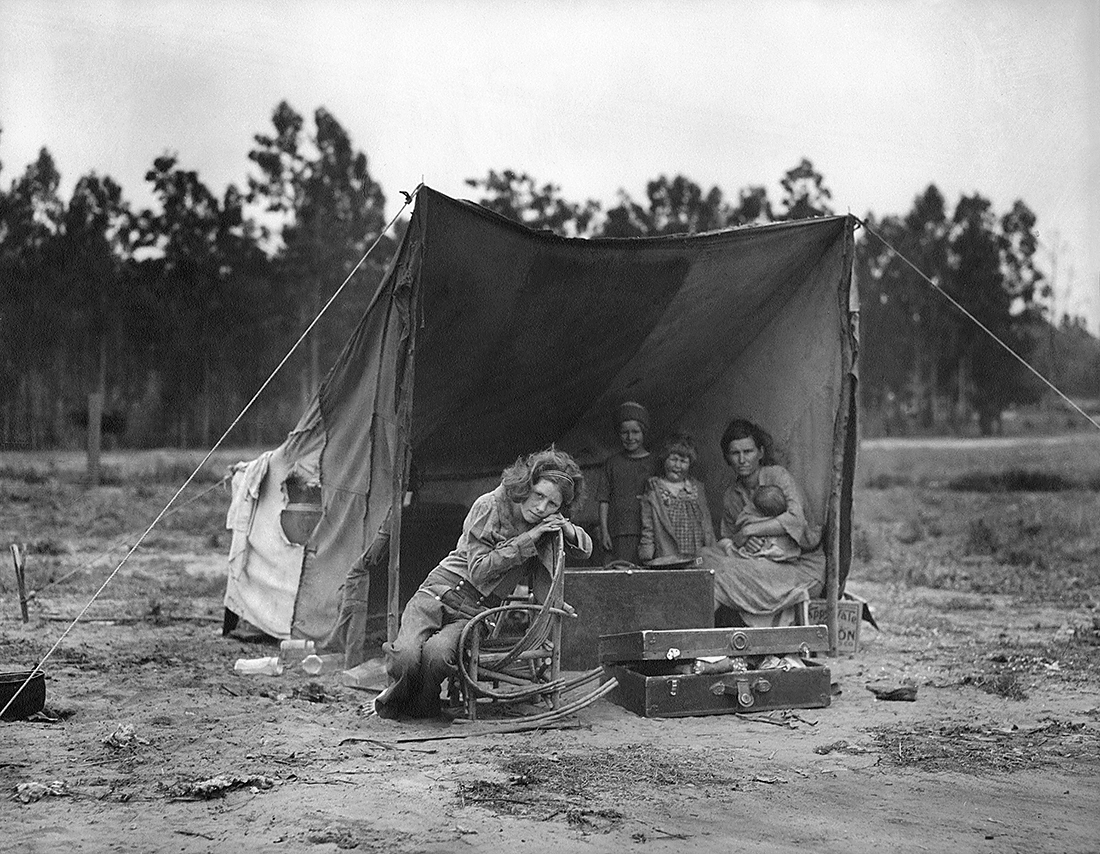

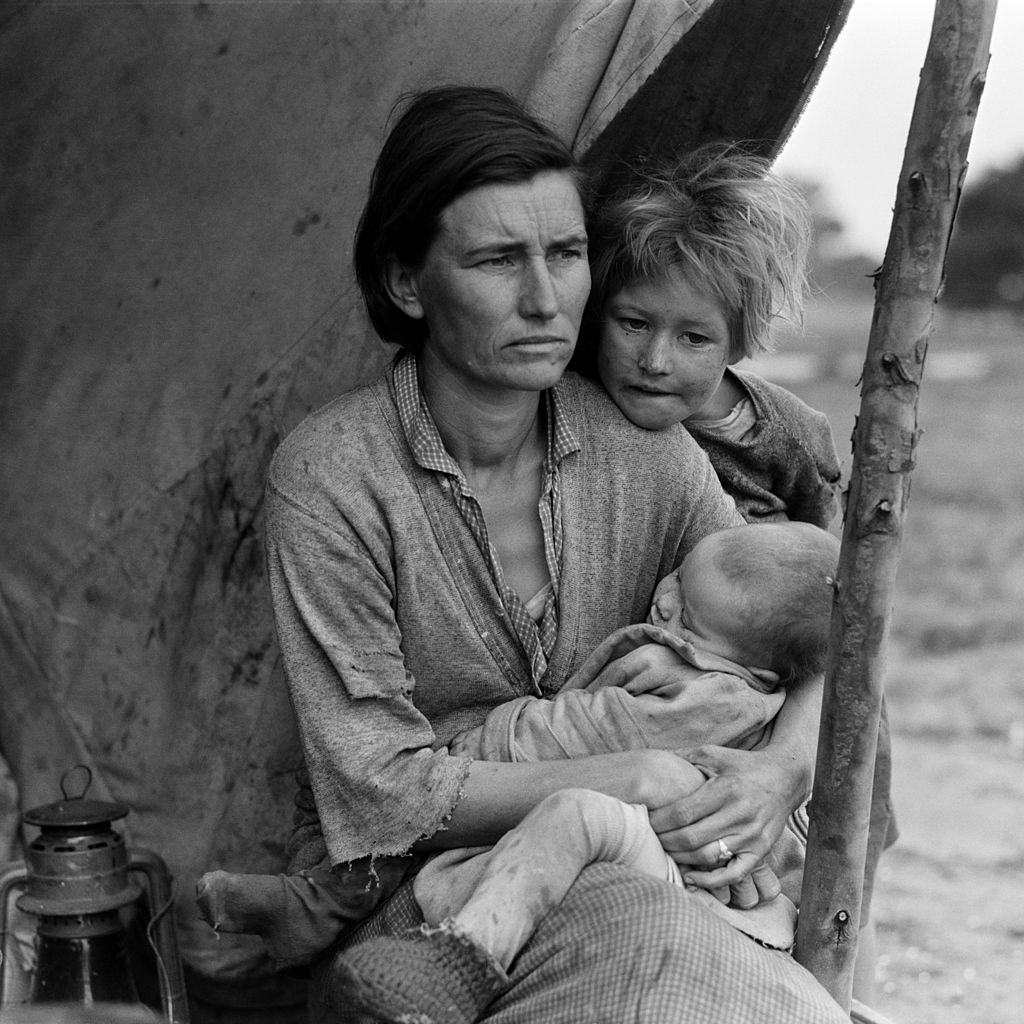

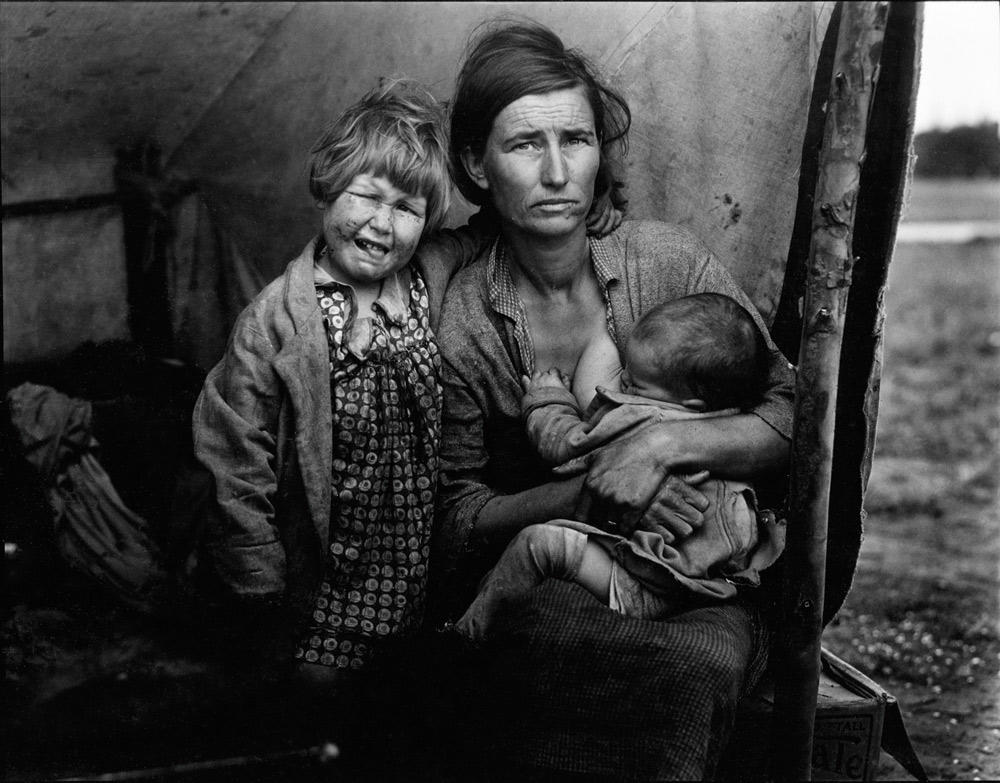

Additional Views of Migrant Mother

Lange made six photographs of the mother and her children. In an interview about the photograph, Lange made this statement on the moment she made Migrant Mother:

I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.[1]

Look closely at the additional images, then consider the questions for looking and discussion below.

Questions for Looking and Discussion

• Why do you think that Dorothea Lange and her boss Roy Stryker chose the tightly-framed image of the woman and not one of the other five images to reproduce and distribute?

• Do the other frames suggest the same narrative as Migrant Mother does on its own?

• Does your understanding of the moment change with more information?

• Do you consider this image to be strict documentation, or do you believe that Lange composed the image to tell a story?

• Why do you think Migrant Mother is now one of the most published photographs in history? What makes it still relevant to viewers?

• Lange did not write down the names of the people in the photograph. Nearly 40 years later, the mother was identified as Florence Owens Thompson, a member of the Cherokee Nation, who had migrated to California from Oklahoma. Thompson later stated that the family had not sold their tires to buy food. Does knowing this information this change the impact of the photograph? What responsibility does the photographer have to the people they photograph in a documentary context?

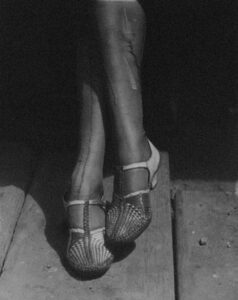

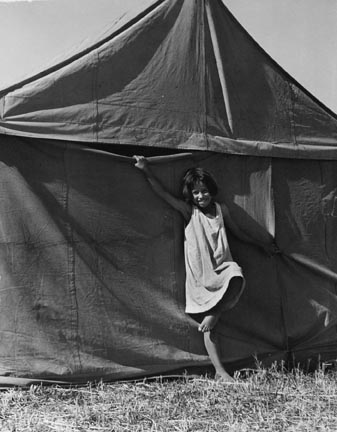

• Why do you think this image became so famous or iconic over time, over another one of Lange’s images, Child in Pea Picker’s Camp Near Stockton, California (seen below)?

Activity: Plan a Documentary Project

The Farm Security Administration photographers of the 1930s and early 1940s used photography to record and respond to great issues of their time such as joblessness, homelessness, and natural and man-made disasters. Divide students into groups and have each group discuss the following questions:

• What are some of the major political and humanitarian issues of our time?

• What are some issues of concern at your school or in your neighborhood?

• If you were to select one of these issues to document through photography, what would you photograph? Why?

• What places, people, or details would you show to tell the story?

How would you make those pictures?

Ask members of each group to share their ideas with the rest of the class.

Activity: What Would You Take?

Many of the families impacted by the Dust Bowl left their homes quickly, taking with them only the few belongings they could fit in their car. They then embarked on long journeys, often not knowing where they might end up and what they might do for work, food, and shelter. They felt pushed away from their homes by poor living conditions and pulled toward lands where they heard there might be more opportunity. Work and resources were scarce everywhere during this time and the migrants were not often wanted or welcome in the places they moved to.

Imagine you must leave your home, possibly forever, and you can only bring what you can fit in your backpack.

• What would you pack? Why?

• What would you want to take? What would you need to take?

• What might you have to leave behind that would be difficult?

• What might you think about and how would you feel as you made these decisions?

Write and draw about what you would take or draw the contents of your bag. Then arrange objects into a still life arrangement to photograph. Please see here for a separate guide on the still life tradition.

Extended Resources

There are many resources on Dorothea Lange, the Great Depression, and the Dust Bowl. A brief guide of recommended sources are below:

High-resolution image downloads

Note: rights to these images are held in public domain by the Library of Congress

Works in Fiction:

Hesse, Karen. Out of the Dust. New York: Scholastic, 1997. Print.

Janke, Katelan. Dear America Survival in the Storm: The Dust Bowl Diary of Grace Edwards. New York: Scholastic, 2002. Print.

Steinbeck, John. The Grapes of Wrath. New York: Viking Press, 1939.

Works in Non-Fiction:

Library of Congress- AMERICAN MEMORY DUST BOWL HOME PAGE

Oakland Museum of California (OMCA) Dorothea Lange Collection

Partridge, Elizabeth. Restless Spirit: The Life and Work of Dorothea Lange. New York: Puffin, Penguin Group USA, 2001

Nardo, Don. Migrant Mother: How a Photograph defined the Great Depression. North Mankato, MN: Compass Point Books, 2011.

Sandler, Martin W. The Dust Bowl Through the Lens: How Photography Revealed and Helped Remedy a National Disaster. New York: Walker & Co, 2009

Guiberson, Brenda Z. Disasters: Natural and Man-Made Catastrophes through the Centuries. New York: Henry Holt and Co, 2010.

Stanley, Jerry. Children of the Dust Bowl: The True Story of the School at Weedpatch Camp, New York: Crown, 1992.

Video:

PBS and Ken Burns: The Dust Bowl Video Clips

Maps:

This map outlines the states considered to be Dust Bowl states and the states damaged by the storms.

FSA Photographs Organized by Region and Photographer

Dust Bowl Timeline (National Drought Mitigation Center)

Audio:

Article / Interview with Daughter of Florence Owens Thompson There are more than 200 interviews of Dust Bo wl refugees in audio file form, available from the Library of Congress.